THE CARLYLE HOUSE

THE HISTORY

The John Carlyle House is a historically significant building, referred to as one of the “great houses” of Virginia. It was built by John and Sara Carlyle in 1752. Credited by many historians as the “birthplace of the American Revolution,” here, five colonial governors met and recommended a policy of taxation without representation, resulting in the Fairfax Resolves. Social gatherings at the House were also attended by key figures in the Revolution, such as Benjamin Franklin, le Marquis de Lafayette, John Paul Jones, and Benedict Arnold.

THE HOTEL AND THE HISTORIC HOUSE

Its stellar history was at one point dimmed by its unique preservation. Between 1803 and 1806, the Bank Building was erected at the corner of Fairfax Street and Cameron Street, right beside the House. Later, in 1849, the Bank was refitted for use as a hotel and called Green’s Mansion House. Six years later, a large four-story addition was made to the Mansion House, which completely concealed the Carlyle House from view.

By 1880, the hotel was renamed the Braddock House and had fallen into disrepair. It was restored and renovated into apartments by H. R. Wager and once more renamed to be the Wager Building. Finally, in 1941, both the apartments and the Carlyle House were purchased by Lloyd Diehl Schaeffer, when he found out the House was scheduled for demolition.

Image Credit

Use the arrows to the left to advance the slideshow.

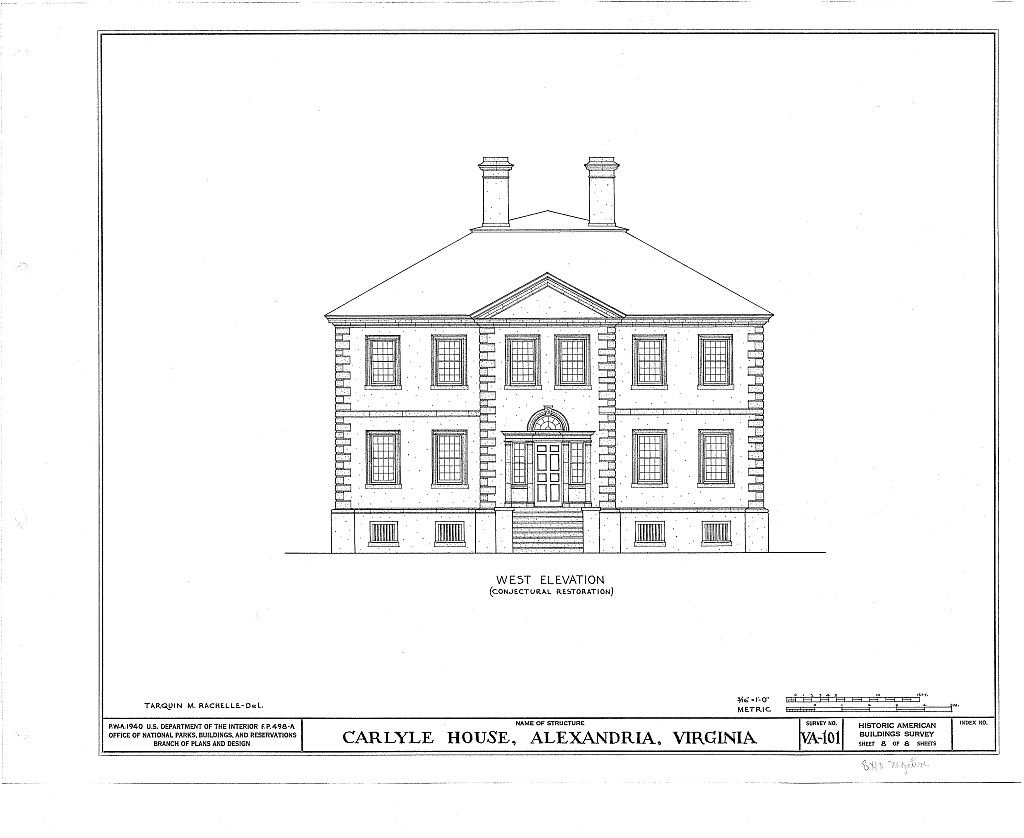

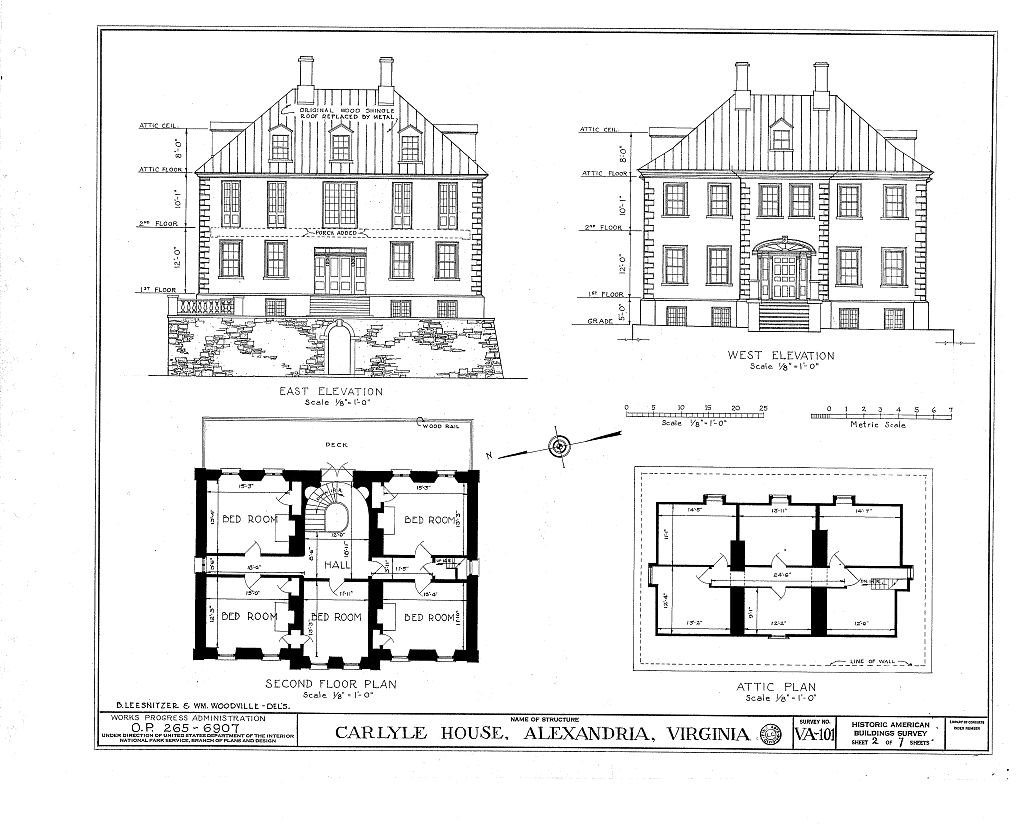

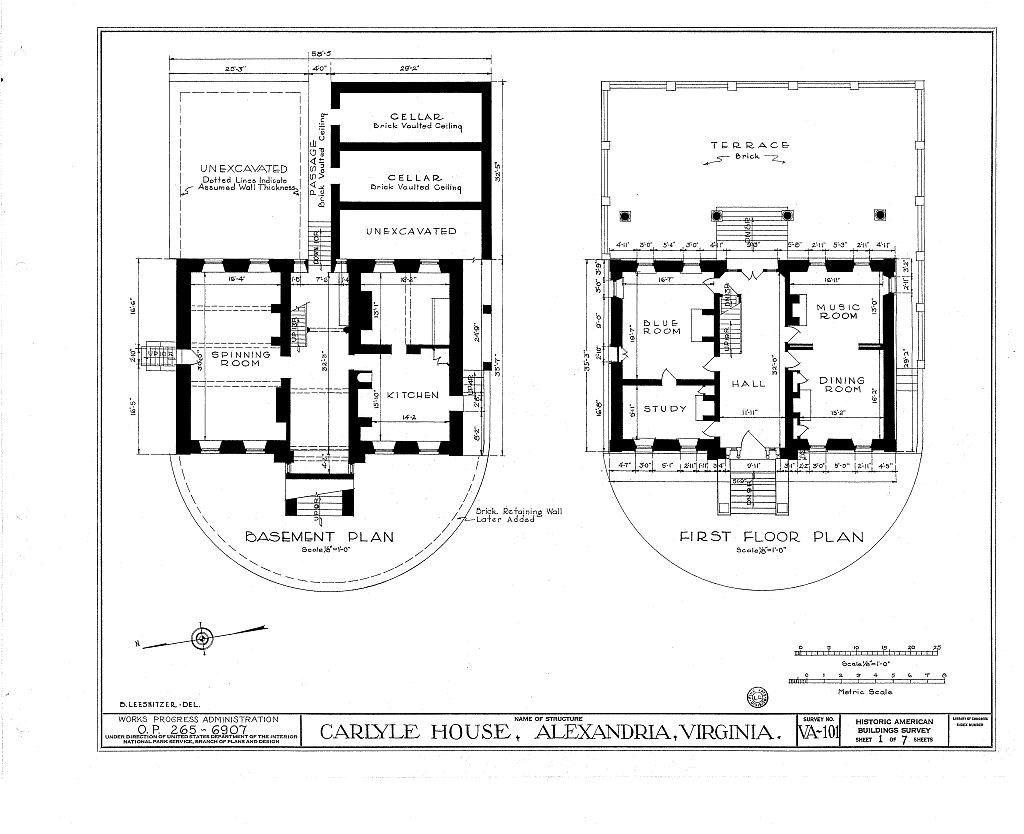

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, HABS VA,7-ALEX,13 [Sheets 1, 2, & 8]

July 6, 1936

The fight to repurpose the house was set in motion by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority (NVRPA) in 1969. This was when Alexandria joined the Authority, who agreed, at the City’s request, to acquire both the Carlyle House and the apartments, now called the Carlyle Apartments. Their intention with this purchase was to create a midcity historic park as a setting for the House.

In 1970, the Executive Director of the Authority, William M. Lightsey, wrote that the Carlyle House possesses the “architectural and historic distinction of a national landmark and that it deserves a showcase setting commensurate with this status.” In order to place the house in the aforementioned park setting, the Carlyle Apartment building had to be removed. Lightsey assured that no demolition would have been undertaken without a “thorough and complete survey.”

Thus, many inspections occurred of the Carlyle Apartments in 1971. None shone a positive light on it. It was said to be in “generally poor condition with inadequate hall lightings and some decay noted on the exterior of the windows.” Notably, there were no ‘exit’ lights in the building to call attention to emergency exits and the sprinkler system was in a state of “serious disrepair.” These factors combined posed a clear hazard to any inhabitants in the event of a fire.

In spite of this clear danger, there was a vocal minority that called for the apartment’s preservation. These opposing values came to a head at the City Council meeting of April 27, 1971.

ARGUMENTS AND RESOLUTIONS

One of the opposition’s speakers, Martin Claussen, a historian and records manager, equated the Apartments to records that were destroyed just because they had not been accessed for a few years. Destruction cannot be undone. He argued that a building such as the Apartments should not be destroyed just because it does not fit the latest architectural decor. After all, the beauty of places like Paris or London is in part the juxtaposition of different eras of architecture all sitting besides each other.

Claussen further argued that the Apartments could be bought and restored by a private investor, and rejected the notion that since “papa city and papa Richmond and papa Federal can’t do it, it can’t be done.” He regards this as “fantastic bureaucratic arrogance.”

In hearing this argument, Vice Mayor Wiley F. Mitchell retorted—

“ … if it had not been for this “fantastic bureaucratic arrogance” of the City of Alexandria the Lloyd House would now be a pile of bricks; the Lyceum would no longer exist; a number of other buildings in this city that have been preserved by the actions of the Council would be no longer in existence.”

He further argues that the Apartments have stood for at least one hundred years, and at no point has any private investor expressed interest in acquiring it.

William M. Lightsey then speaks on behalf of the NVRPA and those in favor of the demolition of the Apartments. They posit that to restore and reuse the Apartments would not have been an economically sound decision, according to a survey done by an investment consultant. The estimated cost to restore the building would have been $2,955,260—in its hypothetical reuse as offices or once more as a hotel or apartment, the annual loss of revenue would amount to $150,000.

Further, the Statement of the NVRPA on the Carlyle House Historic Park Proposal, which Lightsey uses as a source for his arguments, also mentions that the Carlyle House easily qualifies for preservation according to criteria as established by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Register, and the Historic American Buildings Survey. The Carlyle Apartments, in comparison, fails to meet even minimum requirements.

When placed on the National Register of Historic Places in November 1969, the report laments that:

"Unfortunately, the entrance front of the Carlyle House has been completely cut off from the street by the erection of a nineteenth century five-story hotel immediately in front of the house, so that to reach the house one must pass through the hotel, across the moat, and up the front steps."

Similar sentiments come from a 1971 testimony by James W. Colsmith, Chairman of the Alexandria Bicentennial Commission. He notes that there were three buildings involved in the creation of the Fairfax Resolves: the Carlyle House, Gadsby’s Tavern, and the Alexandria City Hall. Whereas the latter two are used and enjoyed daily, the Carlyle House is hidden away from view and inaccessible. Colsmith writes—

“To leave the Carlyle House hidden would be like keeping a magnificent pearl covered within an oyster shell because the shell happened to be a bit unusual. No, let us show this magnificent gem, though we must break the unusual shell to do it.”

In the end, the City Council adopted a resolution stating that, in the effort to create a historic park befitting a uniquely important historical structure such as the Carlyle House, open space must be provided through the removal of the Carlyle Apartments. This would, in turn, improve the public view of the House from Fairfax Street. A demolition permit for the Carlyle Apartments was issued January 18, 1973, and thereafter restoration was underway for the Carlyle House in 1974.

Now, the Carlyle House stands unobstructed in the center of an expansive lawn and garden, inviting visitors to either rest on a bench or enter and learn about the significance of the home.

Image Credit

Use the arrows to the left to advance the slideshow.

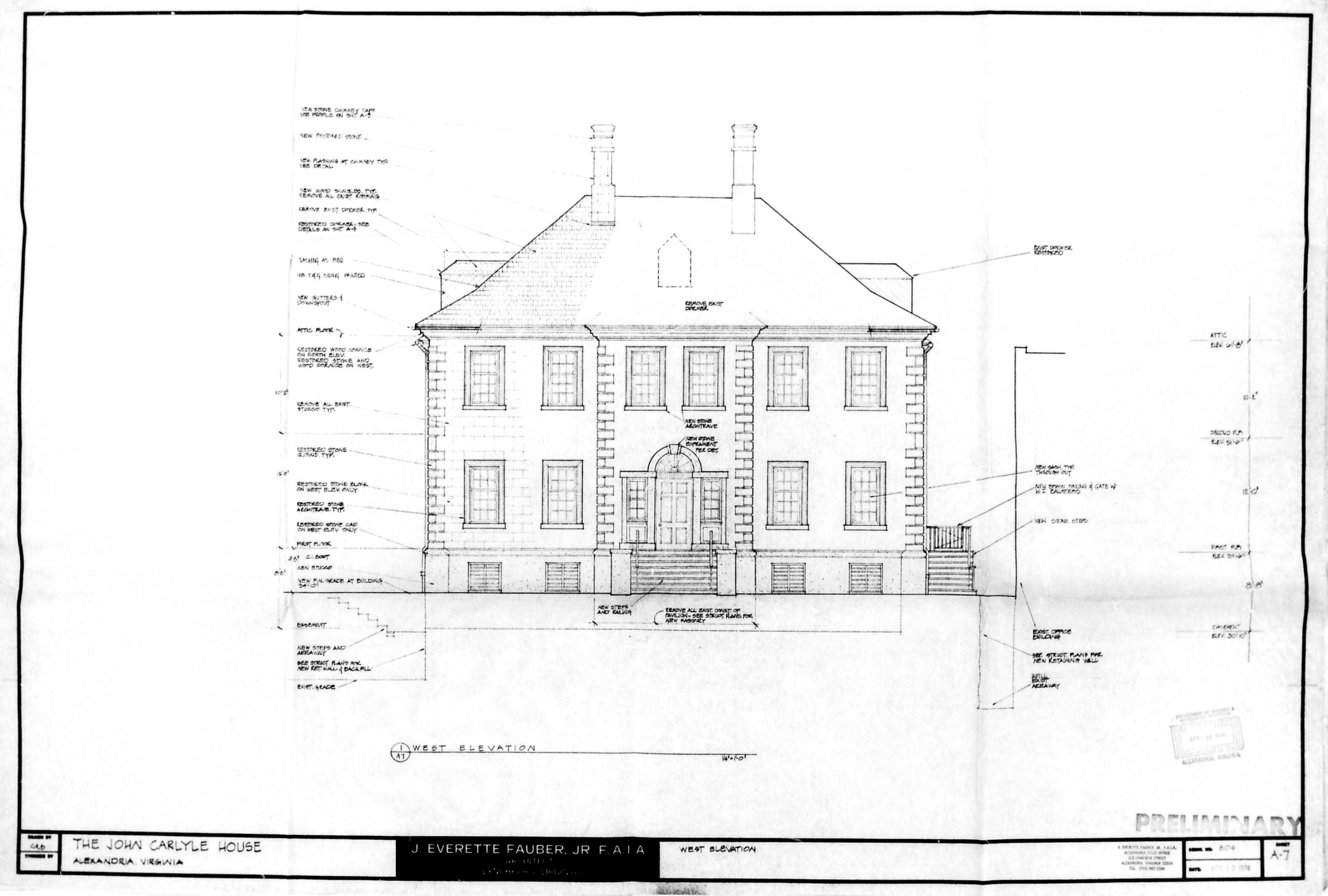

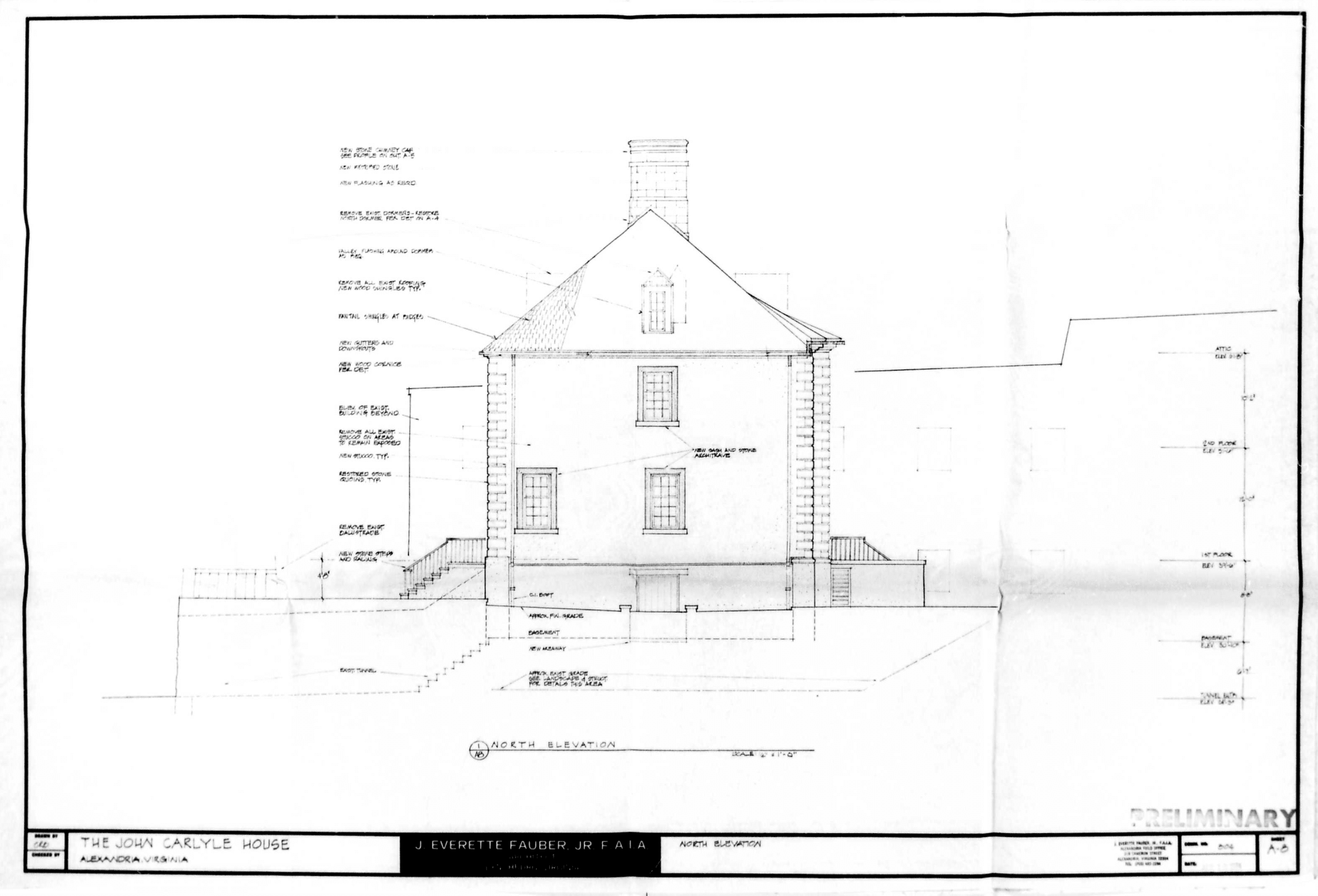

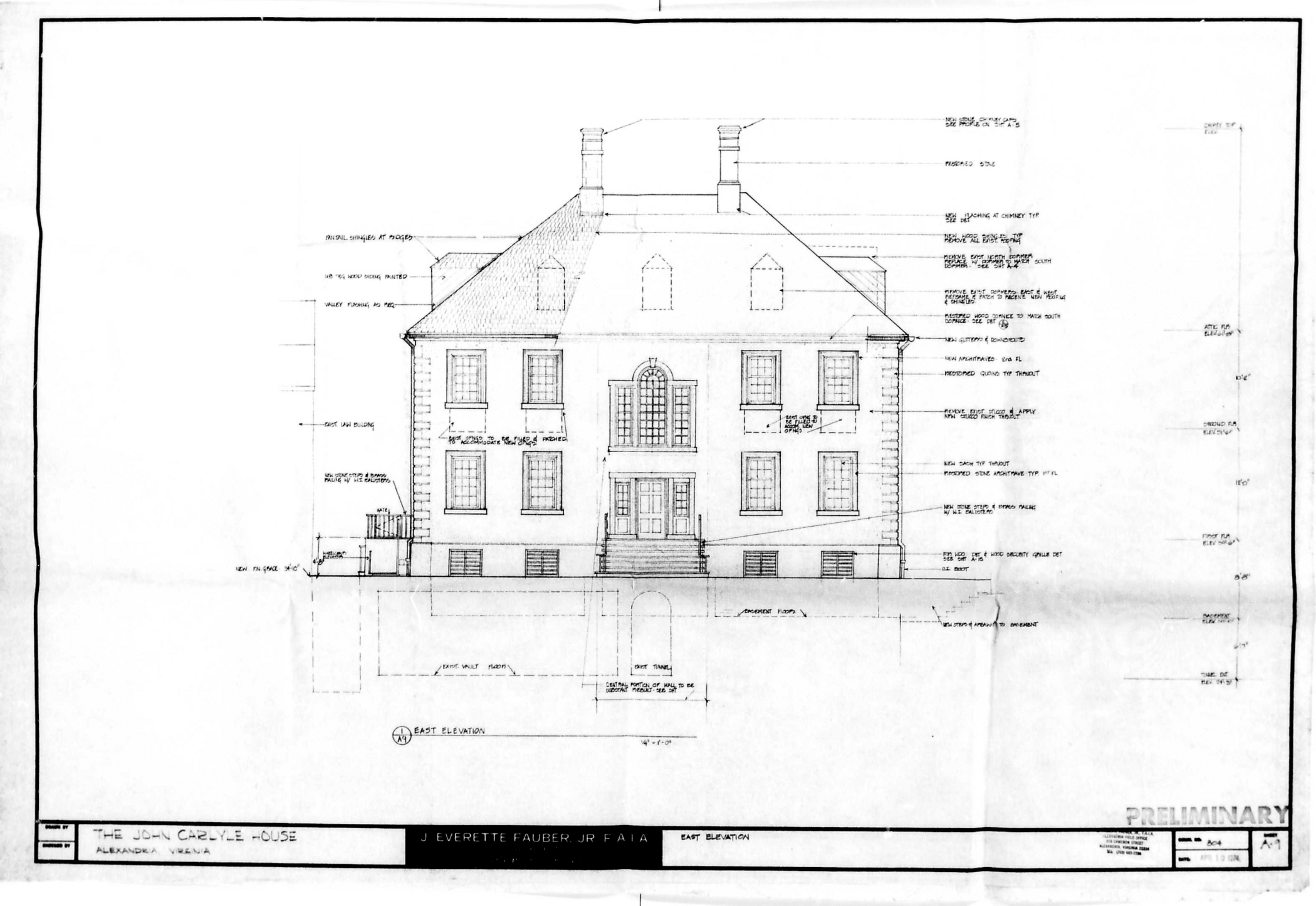

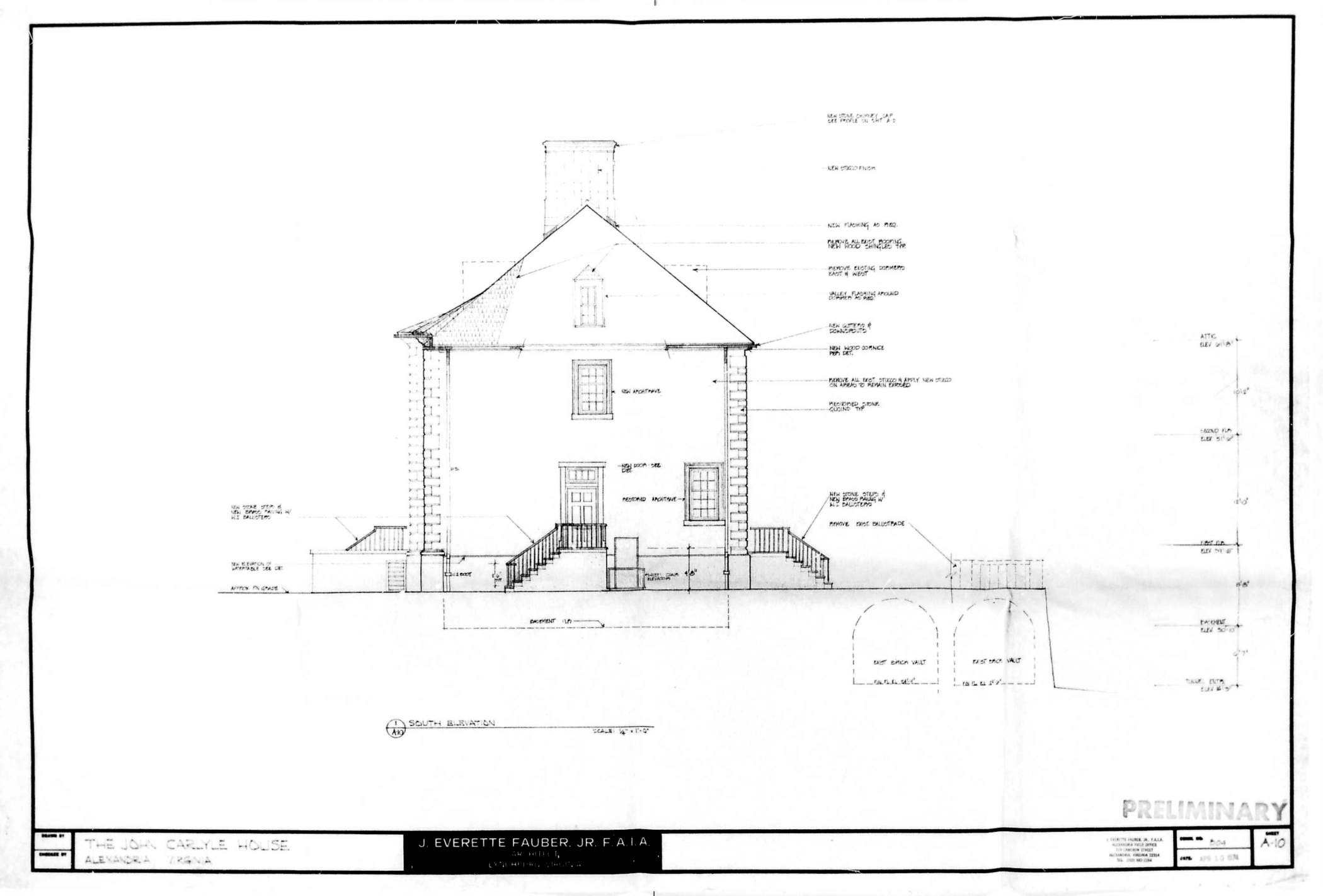

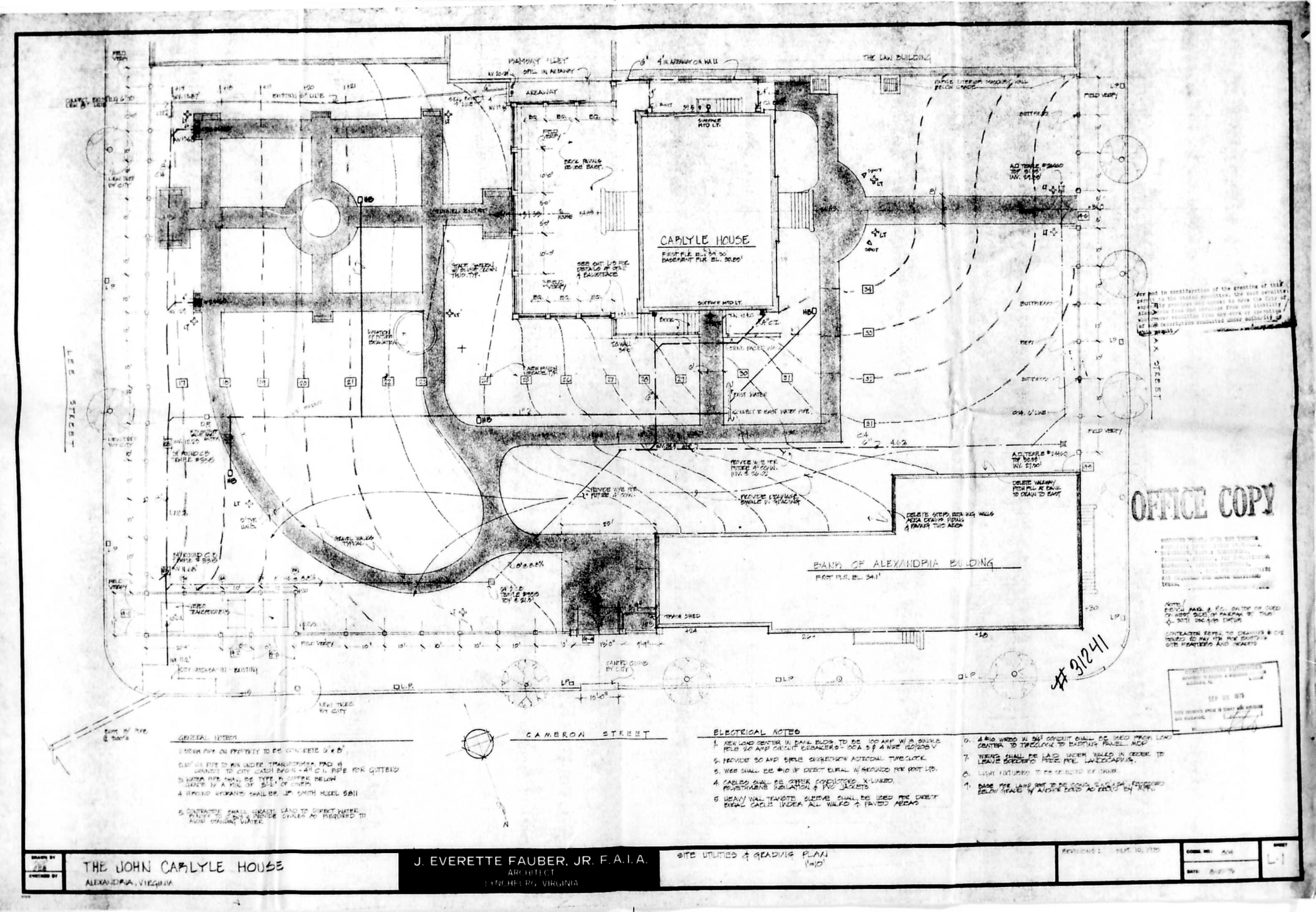

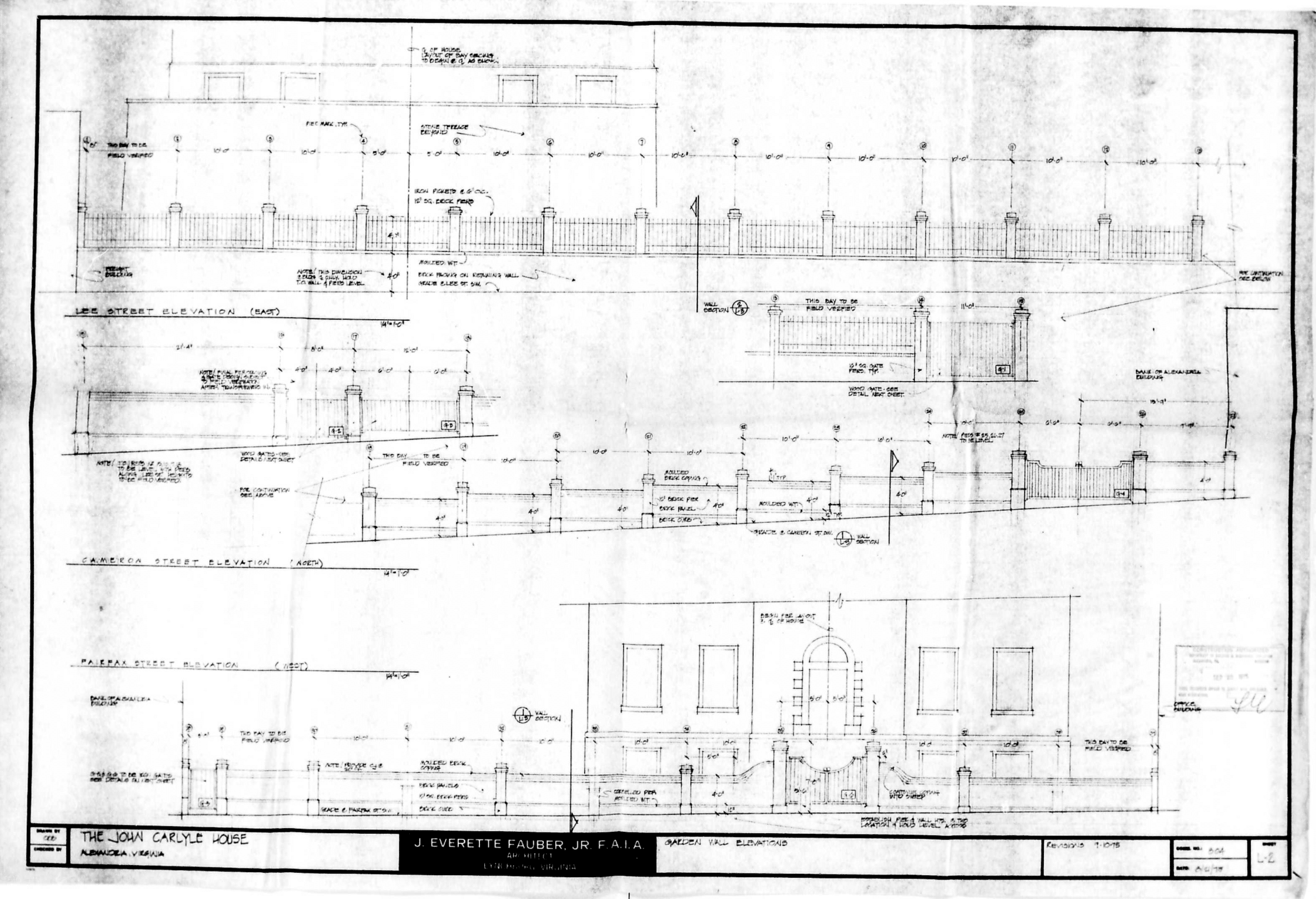

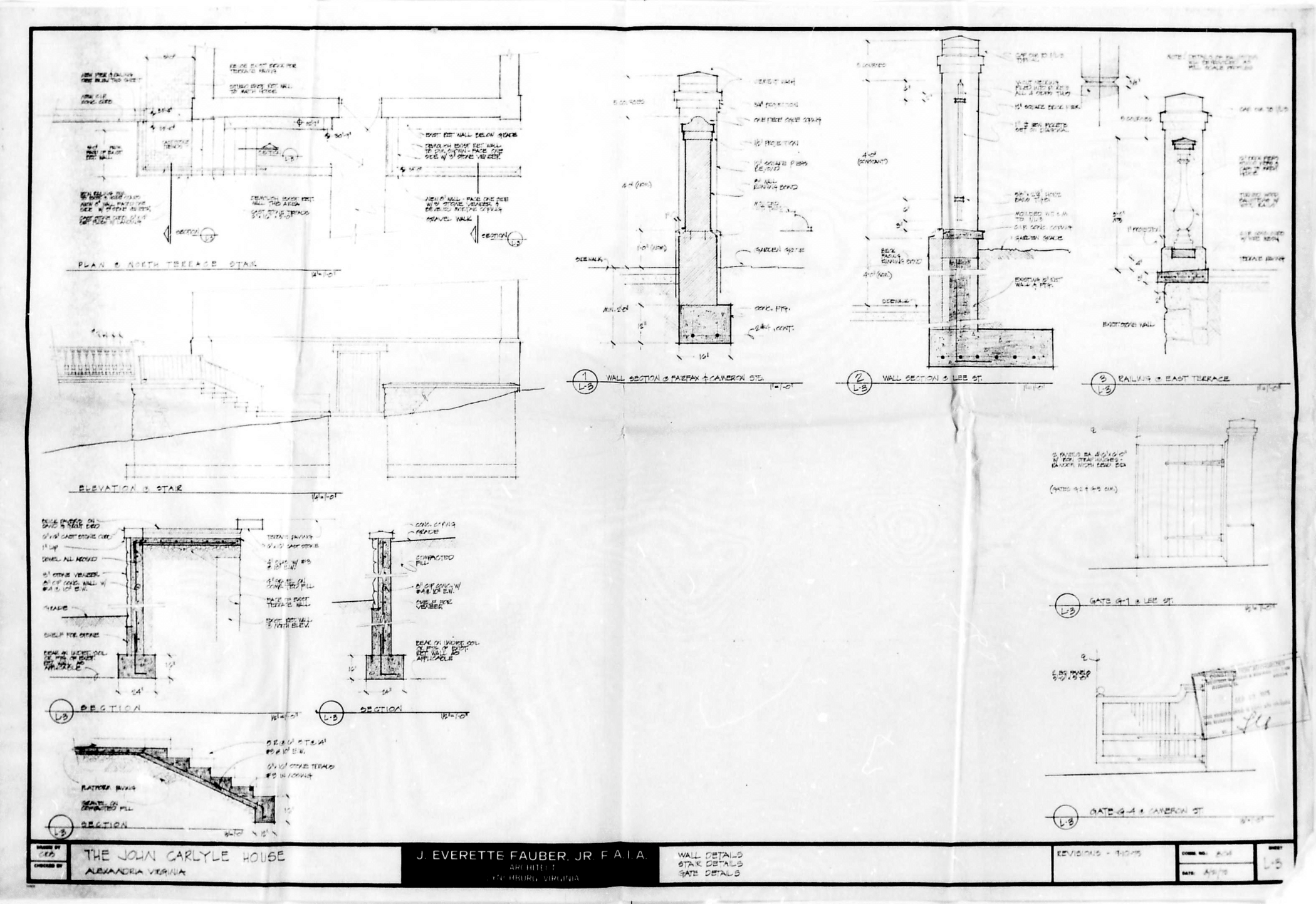

West Elevation; North Elevation; East Elevation; South Elevation; Site Utilities & Grading Plan; Garden Wall Elevations; Wall, Stair, and Gate Details

City of Alexandria Archives and Records Center

THE CITY OF ALEXANDRIA ARCHIVES AND RECORDS CENTER

THE TORPEDO FACTORY ART CENTER